Vision Language Models (VLMs) such as GPT-4o and Claude-3.5 have done well and continue to improve at textual tasks but they still struggle with visual tasks. For example, let’s ask these VLMs to count the number of missing soda cans in this image:

The Soda Can Puzzle Failure

Claude-3.5 (tested on 1/1/2025):

“Looking at the image, I can see cans of Coca-Cola arranged in what appears to be a 4×7 grid pattern (28 total spaces). There are currently 26 cans visible in the image, with 2 empty spaces in the middle of the arrangement. Therefore, there are 2 cans missing from the full set.”

GPT-4o (tested on 1/1/2025):

“To determine how many soda cans are missing, we can count the number of slots in the box and compare it to the number of cans present.

Observations:

The soda box appears to have a 6×5 layout (6 rows and 5 columns), which would hold a total of 6 \times 5 = 30 cans if full. By counting the cans present, I see 28 cans.

Calculation:

The total number of missing cans is: 30 – 28 = 2

Conclusion:

There are 2 soda cans missing from the box.”

Gemini-2.0-Flash-Exp (tested on 1/1/2025):

“The image shows a box of soda cans. There are 24 cans in total. However, there are 2 missing.”

GPT-o1 (tested on 1/1/2025):

“Answer: 12 cans are missing.

Explanation: Based on the arrangement shown, it appears the soda cans were originally packed in a rectangular grid. A common configuration for large packs of soda cans (such as a 30-pack) is a 6-by-5 grid, totaling 30 cans. If we assume the original arrangement was a full 30-can pack (6 cans across by 5 rows deep): The outer “border” layer of such a rectangle consists of:

- Top row: 6 cans

- Bottom row: 6 cans

- Left side (excluding the already counted corners): 3 cans

- Right side (likewise): 3 cans

Adding these up:

- Top: 6

- Bottom: 6

- Left (without corners): 3

- Right (without corners): 3

- Total outer ring = 6 + 6 + 3 + 3 = 18 cans

If only the outer ring of cans remains visible and the entire inner portion is empty, then:

- Total originally: 30 cans

- Currently visible (outer ring): 18 cans

- Missing cans = 30 – 18 = 12

Thus, there are 12 missing cans.”

The soda cans are clearly a 5×7 grid with 4 missing cans. Both models not only get the answer wrong, but they also cannot identify the grid pattern. Furthermore, if you ask them to draw a box around each missing can, they will fail.

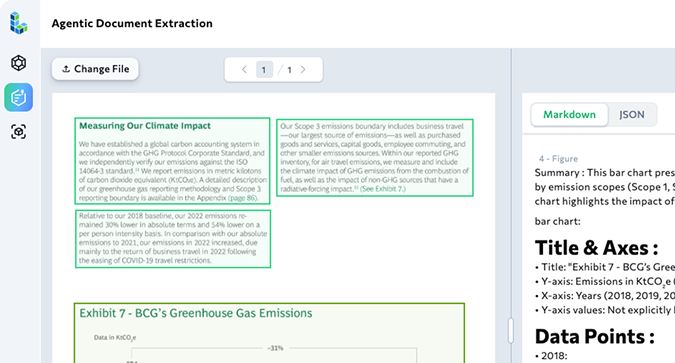

Overview

In this blog post we introduce VisionAgent, an agentic AI framework that can handle difficult visual tasks that require reasoning. In the first part we will introduce the overall agentic framework for VisionAgent and how it modularizes tool choice to pick the best visual tool for a task. In the second part we will show how we can update the model to use design patterns to solve particularly complex visual problems.

An Agentic Approach to Visual Reasoning

To get started, let’s first consider how a human would solve the missing soda can problem. When I solve this task I first locate an empty-looking region in the soda can grid. I then locate cans near the empty region; in this case above and below the regions. To count the number of missing cans I form a sort of grid, so I can see there are 2 cans above the empty spot and therefore the empty spot must consist of 2 missing cans.

Now VLMs are not good at localization, so they likely cannot find an empty-looking region like I did. Because they aren’t good at localization, they also cannot find the locations of the soda cans, but there are many tools that would be able to accomplish this task, such as CountGD. So the first task of the agent could be to find a tool that can locate soda cans.

Given that the agent now has the locations of all the soda cans, it can use this information to construct a grid pattern over all the soda cans. Finally, given the soda can detections, and the full grid, it can simply check if each cell contains a soda can detection; if not, it can be counted as a missing can.

From these steps you can start to see an agentic framework forming. We can break this down this into 3 main components:

- Agentic Tool Selection and Subtasks – The overall problem gets divided into solvable subtasks. For instance, in our running example, the first subtask was formulated to detect soda cans, second subtask for constructing the grid pattern and the final subtask for matching detected soda cans to grid cells to find missing soda cans. For each subtask, optimal tool selection has to be performed agentically.

- Composing Subtasks – We had to compose the subtasks such that the outputs of the previous subtask(s) can be used to solve the new subtasks. For example, to construct the grid we needed the soda can detections from the previous subtask, and to find the missing soda cans we needed the grid and the soda can detections from the previous 2 subtasks.

- Visual Design Patterns – Finally, since VLMs struggle at tasks that require visual reasoning, we need to give the agent a hint by telling it about a design pattern it can use to solve this problem. For example, suggesting that it construct a grid and use the grid to detect missing cans. We will cover this in detail in the next blog post.

Implementing a Visual Reasoning Agent

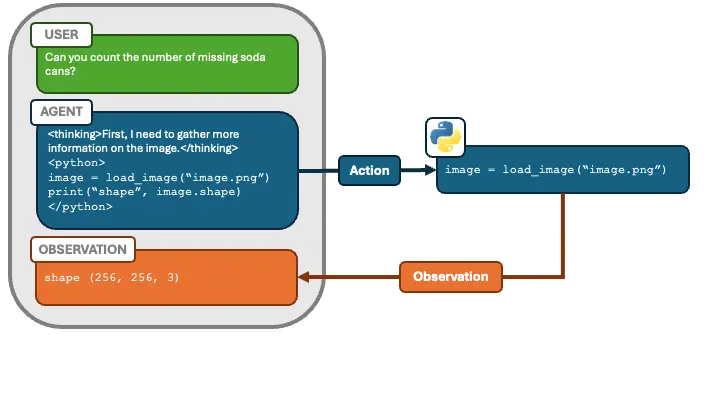

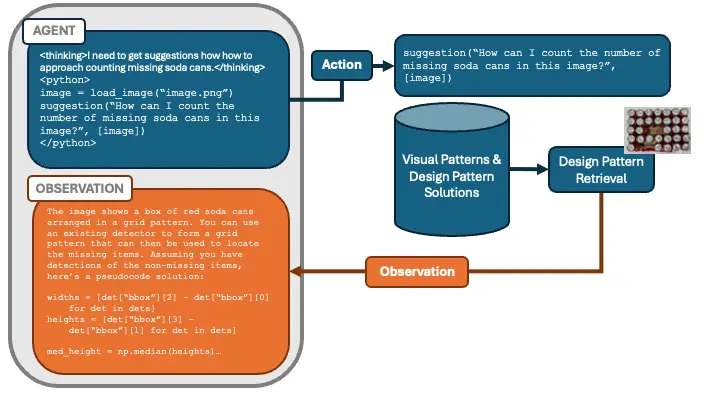

To implement this visual reasoning agent, we need to incorporate the three components mentioned above. Before we do that, however, we need a data structure that can handle both inputs to and outputs from these component–allowing the agent to observe and utilize them seamlessly. One way to achieve this is by borrowing the concept of an event stream from “Open Hands”.

Event Stream Data Structure

An event stream is a structure that:

- Stores user messages and agent messages

- Dispatches actions (like calls to external tools)

- Captures the results or observations of those actions

In the diagram mentioned above, note that the box on the left includes USER, AGENT, and OBSERVATION. Each AGENT message can contain:

<thinking>tags for deciding what to do next,<python>tags, reflecting the approach from the paper “Executable Code Actions Elicit Better LLM Agents”. Giving the agent the ability to execute code (rather than just returning text/JSON) has been shown to improve performance. We let it run these Python snippets in a Jupyter notebook–like environment. We call this main agent the planner agent.

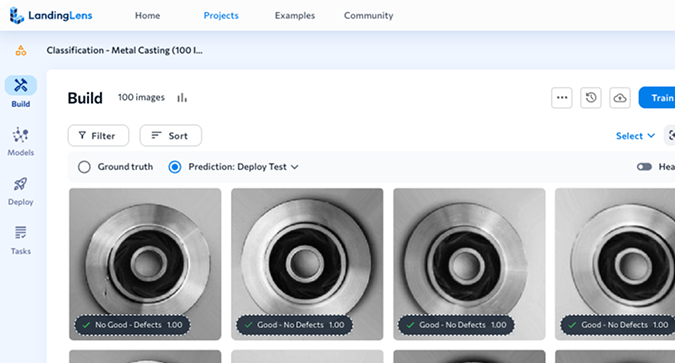

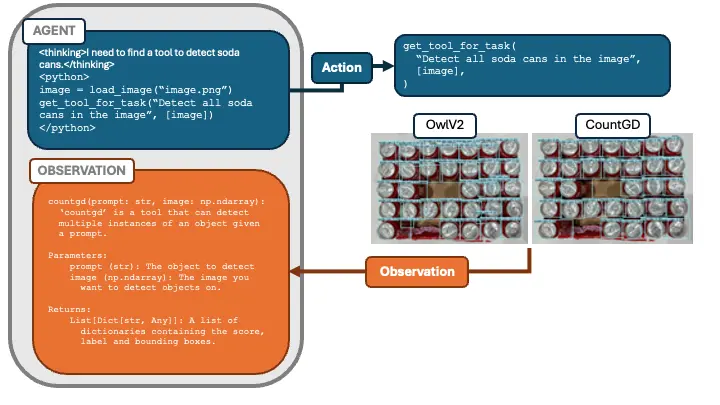

Agentic Tool Selection and Subtasks

Having established the event stream and basic workflow, we can now discuss how to implement the three core components of our Agentic Framework. Referring back to the soda-can example:

- Tool Selection for Detecting Soda Cans The first subtask is detecting the soda cans themselves. We delegate this to a specialized subagent—the tool choice agent—which has access to multiple object-detection tools. Its job is to run these tools on the image and pick the one that performs best for our current task. Since we use code as action, we might represent this by a function

get_tool_for_task(image, description)that returns documentation (or references) for the chosen tool.

The agent uses ‘get_tool_for_task’ to compare multiple detectors (OwlV2 and CountGD), automatically picking the one best suited for soda-can detection.

- Why Tool Choice Matters Selecting the correct tool is challenging, so we handle it in a dedicated tool choice agent. First, the agent interprets the prompt to determine what we’re detecting. It retrieves relevant tools and their documentation, writes code to test each tool on the image, and prints the outputs. A judge agent then compares these outputs to its own approximate prediction.

Note on the Judge Agent: The judge agent doesn’t need to provide an exact count—it just needs to identify which detection result is most plausible based on approximate reasoning. For instance, if the judge guesses 28 cans but sees one tool reporting 5 and another reporting 27, it can rule out 5 as too far off. This allows the system to pick the best available tool without requiring the judge to be perfect. Replacing the judge agent with a human is also an option—sometimes a simple visual check is quicker than labeling everything in detail.

Composing Subtasks

Once we have the right tool, composing subtasks is straightforward thanks to our “actions as code” approach. The planner agent uses Python to pass outputs from one subtask as inputs to the next. For example:

# Step 1: Load the image and pick the best tool for soda-can detection

image = load_image("image.png")

get_tool_for_task("Detect all soda cans in the image", [image])

# Step 2: Use the chosen tool (e.g. CountGD) to perform detection

detections = countgd("soda can", image)

# Step 3: Create a grid pattern based on the detections

grid = create_grid_pattern(detections)

This modular setup makes it easy to debug each stage. If the detected boxes look incorrect, the planner can try a different confidence threshold or switch to another tool. Because each action is executable Python code, the process of re-running or re-parameterizing is smooth and transparent.

Visual Design Patterns

The final component is visual design patterns. We implement this by giving the planner agent a special action called “suggestions,” which serves as a lookup for known design patterns relevant to our problem. The planner agent submits a prompt and image, receiving a ‘visual design pattern’ suggestion if a suitable one is available.

What are Visual Design Patterns?

Before we dive into the details of this component, it’s important to set some context. If you’ve ever worked on Visual AI projects, you’ll probably know that there are certain visual patterns in images and problems that you can identify and use to draw from a pool of techniques that can be used to solve those problems. Take for example the visual grid pattern and the corresponding design pattern of using an object detection model to construct a grid and identify missing objects. This same pattern actually pops up in many different situations:

So you can see how having a design pattern to solve one type of problem can be applied to many use cases.

Visual Design Pattern Implementation

To build the visual design pattern component we have labeled different images and user questions and their corresponding design patterns used to solve them. The component works by taking in the target image and a query, generated from the planner such as “How can I count the number of missing soda cans in this image?” The component then decides if the image and query meet one of the visual patterns we have labeled. If so, it retrieves the design pattern solution, which is a pseudocode solution on how to solve a problem containing that particular visual pattern. This is then returned back to the planner discussed in the previous blog post.

For example:

- A user prompt might say, “Identify how many cans are missing in this regular grid.”

- The suggestions action checks if any known pattern (like a grid-based arrangement) applies.

- If it matches, the action returns a design pattern outline: “Use the detected bounding boxes to infer grid cells, then compare each cell to see which are empty.”

- This approach helps the planner agent tackle more complex tasks by following structured strategies—especially when straightforward detection alone isn’t enough.

Below is an example of a design pattern used to locate different sized objects. You can see it’s a pseudocode prompt that can be sent to the main planner agent to help it solve the problem. Tools are not explicitly stated but instead wrapped in carrot brackets with a description of what’s needed. This way it’s free to choose any tool that can accomplish the task described in the carrots.

# You are trying to order objects into comparative buckets, such as small and large, or # small, medium and large. To do this you must first detect the objects, then calculate # the bucket of interest (such as area, circumference, etc.) and finally use a # clustering algorithm to group the objects into the desired buckets. You can use the # following code to help with this task: from sklearn.cluster import KMeans import numpy as np detections = <a detection tool that also includes segmentation masks>("object", image) def get_area(detection): return np.sum(detection["mask"]) areas = [get_area(detection) for detection in detections] X = np.array(areas)[:, None] kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=<number of clusters>).fit(X) smallest_cluster = np.argmin(kmeans.cluster_centers_) largest_cluster = np.argmax(kmeans.cluster_centers_) clusters = kmeans.predict(X) smallest_detections = [ detection for detection, cluster in zip(detections, clusters) if cluster == smallest_cluster ] largest_detections = [ detection for detection, cluster in zip(detections, clusters) if cluster == largest_cluster ]

The challenge with visual design patterns is feeding the planner the correct design patterns when solving a problem. Too many unncessarily design patterns can confuse it and if you don’t get it the correct pattern it can lead to a failure.

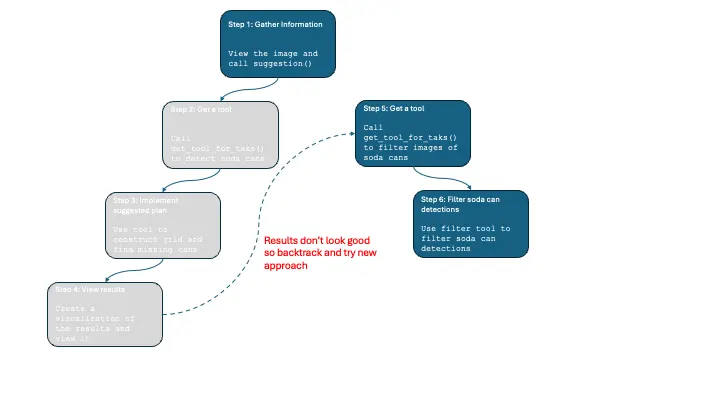

Putting it All Together

Now that we have covered all 3 components: agentic tool selection and subtasks, composing subtasks and visual design patterns, how do they all work together? We give the planner agent a budget of 10 steps to make when trying to solve a problem, and we also give the planner the ability to use libraries like Matplotlib to plot and visualize results. This allows the planner to go down a path, decide it doesn’t like the results, and then backtrack and find a new path. For example, the planner could use the plan we have described in this blog to find soda cans, but after visualizing the results decide that CountGD did not do a good enough job. It can then backtrack and find a tool to filter the CountGD results such as SigLIP, and then start a new plan where it crops the CountGD objects and filters them with SigLIP to improve performance.

With these components and agentic workflow in place we can now better reason about vision tasks.

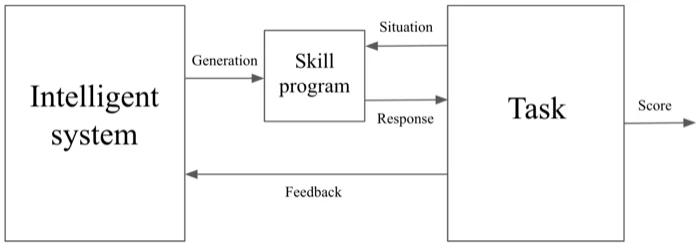

The approach we have taken with VisionAgent can be seen as program synthesis, a topic discussed in Francois Chollet’s On the Measure of Intelligence paper, where an intelligent system generates a “program” that can be used to solve a task.

Here, VisionAgent is the “Intelligent system” and the program it generates for a given task is the “Skill program”. Our tasks are different in the sense that they are vision problems so they do not produce a response or score. However, you can also think of our tasks as the human evaluating the VisionAgent solution, who can provide a response to VisionAgent if it does not perform the task correctly or evaluate it with a score

Conclusion

In this blog post we covered how to use visual design patterns to further enhance our agents visual reasoning skills. We can do all sorts of cool things with this in addition to just finding missing soda cans, such as tracking a queue ball in a pool game, or counting the number of smaller screws on a table. You can checkout the source code https://github.com/landing-ai/vision-agent if you want to play around with it for yourself. Here’s a few more examples of what VisionAgent can do:

Prompt: Count the number of missing soda cans and draw a bounding box around them.

Prompt: Count the smaller screws in the image.